Nina Powles revisits her childhood obsession with The Saddle Club series and finds their appeal, though flawed, remains.

There was one book in the school library that I got out so many times I knew its exact place on the shelf. The cover had a wild horse on it, its mane and tail flowing in the wind, standing in a field of tall grass beneath a sky streaked with clouds.

I can’t remember the book’s title, only that it was about a wild horse that lived somewhere in the plains of North America. It’s like this with some books from when we were young – the titles don’t stick, but the pictures and colours have been burned into our memory.

My collection expanded as I discovered Black Beauty, Misty of Chincoteague, Joy Cowley’s Shadrach series, and a bunch of non-fiction books about horses and horse care. I even begged my mum to let me have an ancient edition of The New Zealand Pony Club Manual that I found at a secondhand bookshop in Levin.

The famous forerunner of the pony book genre, Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, was published in 1877. Pony books like the ones we know today – that is, children’s books exclusively about riding and caring for horses and ponies – became popular in the late 1920s with The Young Rider by ‘Golden Gorse’, the pseudonym of English children’s author Muriel Wace (1881-1968). It seems like pony books have been popular with young readers, mostly girls, ever since.

Perhaps this picture of an ideal girlhood spent taking care of your own pony, riding through meadows and winning ribbons at shows stems from the English tradition of horse riding as an ideal pastime, a symbol of upper-class propriety. The work involved in caring for your own pony also aligns neatly with the outdated notion of educating girls to become carers and nurturers. Some conventions of the pony book genre even feel like echoes of domestic trappings: the intricate details of caring for a horse, the repetition of daily stable tasks, the emphasis on outward appearance, the discipline and decorum required for learning to ride.

The world of the pony book promised freedom, adventure, independence, unbreakable friendship and, above all, belonging.

But the modern pony books I read and loved presented something different. Here were girls on horseback rescuing their friends from danger, girls working together to solve horse-related mysteries, girls riding out alone into the wild with nothing to fear. The world of the pony book promised freedom, adventure, independence, unbreakable friendship and, above all, belonging.

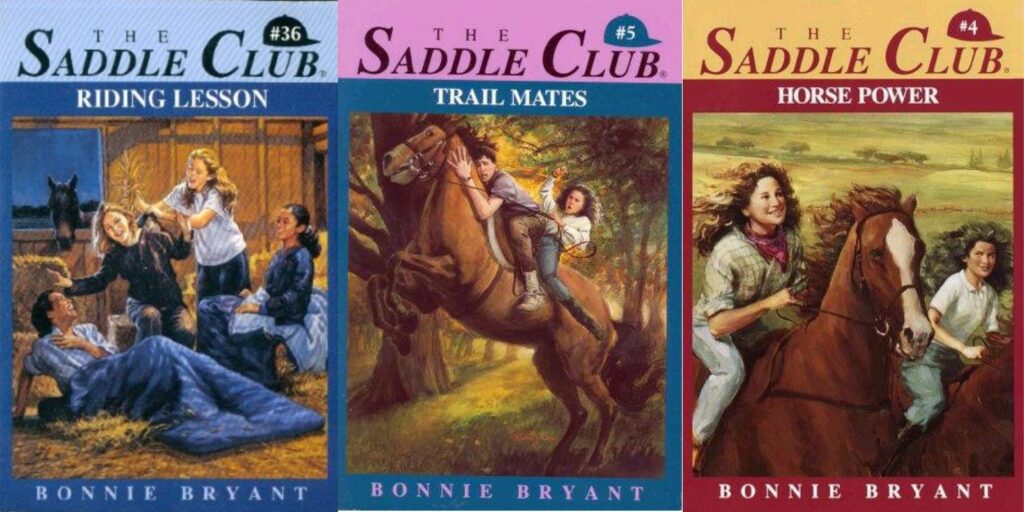

My obsession with horses reached its height with The Saddle Club series by American writer Bonnie Bryant, published between 1988 and 2001. When I was ten or eleven I collected and read all 101 books. The series follows best friends Carole, Stevie and Lisa, who live in suburban Washington D.C. and take riding lessons at Pine Hollow Stables. The rules of the club are outlined within the first few pages of every book: ‘Rule number one: you must be crazy about horses. Rule number two: you must be willing to help the other members out, no matter what.’

I found a Saddle Club book at the library (my mum gave my collection away years ago) with the aim of re-reading just one of the books for research. Instead, over the course of three days, I poured through six titles: Trail Ride, Horse Love, Horse Whispers, Phantom Horse, Horse Trails and Tight Rein. As soon as I finished one, which took two hours at most, I went onto the next. I read on the bus, I read in cafés, I read while cooking dinner. Even when the plot got ridiculous (as in Horse Trails, when Lisa gets chased through a canyon on horseback after stumbling across poachers stealing fossils from an archaeological dig) or the cheesy dialogue got excruciating, I couldn’t stop. I needed more trail ride adventures, more stable mysteries, more boy drama. More escape from my own life, which included approximately none of those things.

I needed more trail ride adventures, more stable mysteries, more boy drama. More escape from my own life, which included approximately none of those things.

Although some pony book readers must be girls who already own ponies, they are a select few. The rest of us are on the outside looking in, eager to be part of the secret club, to be let into this world that remains distant and mostly inaccessible in real life. A place we could only go in our dreams, or in books.

But isn’t it possible that there might also be appeal in the predictability of these stories? After all, for most kids and young teens, reading is an escape from the instability and uncertainty of growing up. A considerable amount of children’s and young adult fiction can be categorised as ‘genre fiction’, the type of books we tend to sneer at as adult readers. More than half of the Saddle Club books were, in fact, not written by Bryant herself but by a team of ghostwriters, a testament to just how formulaic they are – with a sound knowledge of the previous books and a keen interest in horsemanship, almost any writer could create one. But genre is so crucial to how we read as kids, and therefore shapes how we read (and perhaps write) as adults, too. The first questions were always: What do you like to read about? What kind of stories do you like?

Maybe it makes perfect sense that I found myself suddenly hooked on these books again at 23 years old. The Saddle Club traces a brief, magical period in the course of our growing up before the complications of teenagehood set in. That period defined by secret hideouts, first crushes, sleepovers spent whispering in the dark. Those years that feel frozen in time yet simultaneously seem to pass too quickly. For the Saddle Club girls, time is frozen – Lisa, Carole and Stevie remain 12–13 years old for all 101 books in the series.

The Saddle Club traces a brief, magical period in the course of our growing up before the complications of teenagehood set in.

But the version of girlhood portrayed in The Saddle Club is not always carefree. There are passing mentions of one of the girls, Lisa, recovering from an eating disorder: ‘It made Carole happy to hear Lisa sounding enthusiastic about eating. Unlike Stevie, who basically lived to eat, Lisa had more complicated feelings about food,’ (Horse Whispers). When the narration slips into Lisa’s voice, there are repeated mentions of hunger, appetite and self-conscious thoughts regarding her eating. Over the course of the series we learn that Lisa has a difficult relationship with her mother, who believes in ‘proper ladylike behaviour’ and often comments on her daughter’s looks.

I like to think it’s no coincidence that it’s Lisa who in Trail Ride experiences one of the few moments in my re-reading of these books that made me pause and take a breath to let the gentle shock of it pass through me: ‘During the struggle to reach the other side of the trail she had bitten her lip. She laughed, enjoying the salty taste of blood. It reminded her that she was still alive.’

Boys break hearts, parents divorce, beloved horses die or get taken away. The one constant is the girls’ friendship. That elusive perfect trio of best friends that is so hard to come by and so easily disrupted by factors we can’t control.

Bonnie Bryant went on to write another series set three years after the events of The Saddle Club called ‘Pine Hollow’ that follows Stevie, Lisa and Carole into their teenage years. I never read it, since by the time I reached high school I had ideas I should be reading ‘real’ literature like Wuthering Heights and Catcher in the Rye. But now I just might.

Nina Powles

Nina Powles is a writer from Wellington. She holds an MA in Creative Writing from Victoria University and was the 2015 winner of the Biggs Family Prize for Poetry. Her work has recently appeared in Mimicry, Scum and Shabby Doll Houseas well as several self-published poetry zines. Her debut poetry book, Luminescent, was published in August 2017. She is half Malaysian-Chinese and currently lives in China.

Blog: dumplingqueen.weebly.com

Website: ninapowles.weebly.com